This piece was written by Melanie Kent during our Unspoken Ink: Creative Writing Workshop.

“My demographic,” I told my sister. “Can we say ‘my demographic?’”

It was code, so that when we navigated the Covid-tightened New York sidewalks, chatting almost directly into others’ ears, it didn’t have to be “cancer” that they heard, “cancer” that I shared, like a little poisonous puff of fumes on the air.

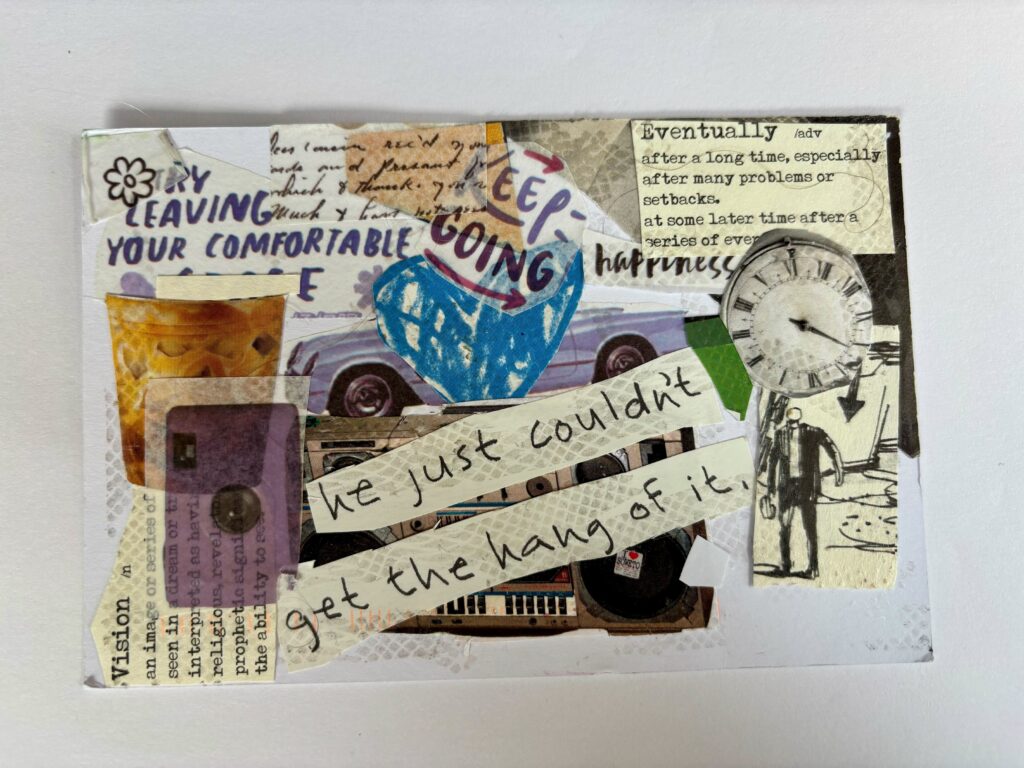

It was also partly that “young adult cancer survivors” was a lot of syllables. And that I didn’t like the shorthand I’d discovered: “AYA,” for adolescents and young adults with cancer. It sounded too much like a club I was a member of, like the YMCA. But the main reason was that saying “cancer” still felt like pronouncing one of those subtle Arabic or Lao sounds in my mouth knowing I had got it wrong: unfamiliar and shaming. And it felt dangerous, and bizarre, like a spoken password to a toxic sci-fi fantasy world, or a curse word drenched in a drug that makes you dissociate when you swallow it and tastes clinical and cold and bitter like the iron in blood.

I didn’t want any claim on the “AYA community.” “My demographic” kept some distance, the same kind you use to chart casualties in Excel.

I remember at the beginning, my oncologist mentioned she could put me in touch with someone who had my kind of cancer and was also young. It sounded like a truly horrible idea. Talk with someone who could die too, who reflected back to me everything that was horrible about what I was dealing with? No way.

A friend of a friend commented that her niece was in New York at my same treatment center, and she would be happy to connect us, and that would be so great. She messaged again, twice, when I didn’t respond. The very idea made me feel so overwhelmed I burst into tears. How could I manage to bear anyone else’s experience of this? How could I be expected to carry that? What could be worse for me right now? To a small, bitter piece of me, it seemed like a selfish impulse, playing hooky with helplessness to fix an unfixable thing. Like two sads could equal a happy and she could get the satisfaction of feeling none of it except the pat on her back.

It was an extension of the cancer stories that got piled on me that first month: of a classmate’s aunt, a colleague’s grandmother, a friend of a friend of a friend. They would name the diagnosis, the result, a couple details about the struggle. Obviously, they’d stick only to the stories of those still alive, but they’d share them like they were somehow good for me. This person has cancer; they are living, so. The subtext: be encouraged?

I hated those stories, with a hard H, with a sharp T. They exposed me. Cut straight through to my fears and underlined all my unknowns. They shed no light at all on my chances. Comparison was as irrelevant as bringing up someone’s odds on the moon. What it did do was ignite the huge question mark over my life in crazy neon colors. The stories would flood my tired mind with others’ trauma, and every detail about doses or prognosis landed like a punch to the gut. I was too raw not to feel it—the pain. That, I did have in common with these people. I did not need more.

I did not even want to think about the existence of other cancer people. Forced proximity with fellow patients was hard enough. I learned to put in earplugs every second of the eight-hour treatment sessions, popping them in before I even entered the lobby. Any stray comment had an absurdly cranked-up chance of being the most personal, difficult, high-stakes thing you could imagine. I’d hear and register them as pieces of my altered reality, like the voices were painting high-def twisted trees or cliffs or whirlpools onto the dark, blurry landscape of my new world.

“I would rather be six feet under than have a drain like this, do you understand??”

“It’s my daughter, she’s six. She’s projectile vomiting. I’ve been here all night.”

“It’s my sixth cancer, you know, and…”

“That option would be like winning the battle but losing the war.” “Yes.”

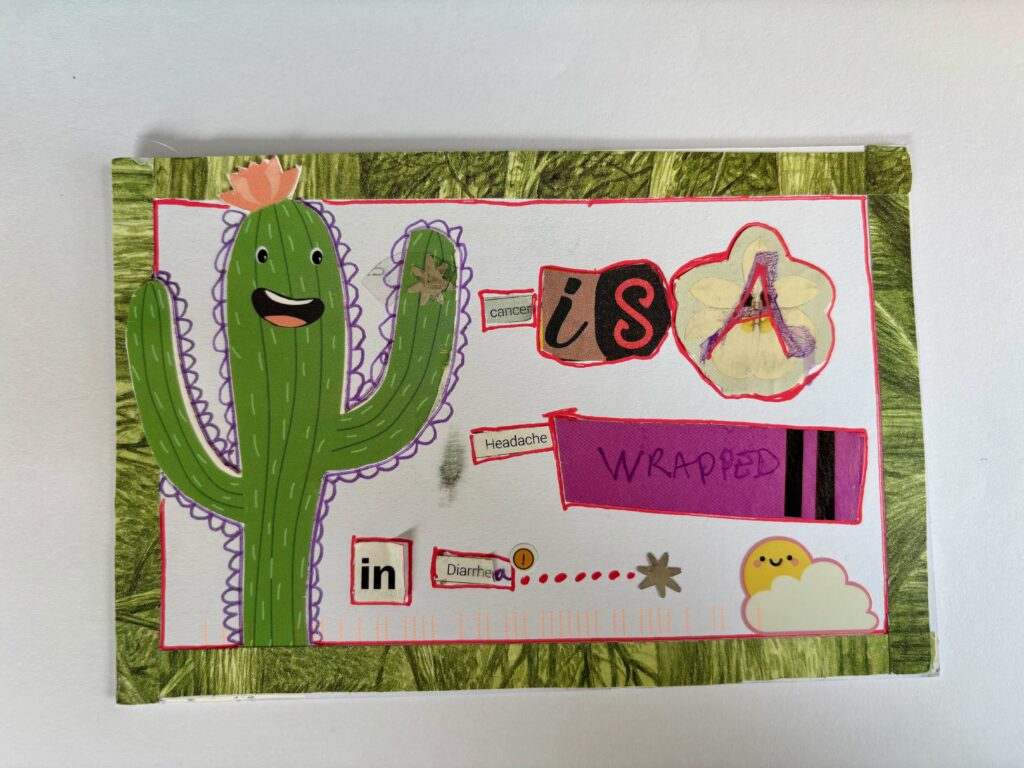

The idea of a “support group” where you talk to “other survivors” sounded to me just like the picture in your head: the scariest kind of depressing—a bunch of bald dying people in hospital gowns on zoom talking about how horrible it is to be bald and dying. Or (maybe more grotesque), pasting smiles on their faces and high-fiving each other, all pumped up about finding what really matters in life and being strong and brave and inspirational.

I didn’t think I could take it. But it wasn’t just denial and triggers and caricatures that got in the way of me connecting.

It was the idea of being friends with people who were much more likely, statistically, to die earlier than normal, and to have very difficult things happen to them. It was the risk that everyone I knew was weighing with me: how closely do I want to be entwined with that kind of hard?

It was seven months into the diagnosis, past chemo and surgery and just before radiation, when my dad took me to the treatment center for my second Covid vaccine dose. We came out to the curb and stepped toward a car we thought was our Uber. “Trying to steal our ride?” A guy on crutches grinned at me. His brother rolled open the door while we craned our necks for the next car. I smiled to myself out the window on the way back. He was cute. He was recovering from surgery just like me. I liked his style, his skinnies. I wanted to know him, to be friends. To talk about crutches and crushes, about movies and food, how his brother talks to him about it, what he says to friends.

This is the part where the movie would have the two of us fall in love and be adorable and also vaguely tragic.

But my life isn’t a movie (and I never saw that guy again). What happened was I made cancer friends. Because they know the risk and chose me anyway, but mostly, because I like them and we have fun. We do talk about dying and what matters in life. We talk about toxic positivity and triggers, scanxiety and grief, memes and insurance, jobs and dating. We talk about the patterns and points of tension under all the sticky mess of a cancer culture that’s shaped by everything from movie plot lines to Facebook tributes to fundraising strategies. We talk about how to talk about cancer. We talk about us, and we talk about you.

I needed denial at the beginning. I needed distance. Sometimes I still do. But what changed when I saw that guy by the Uber was I saw him, not a cancer patient.

It meant I could see me too.