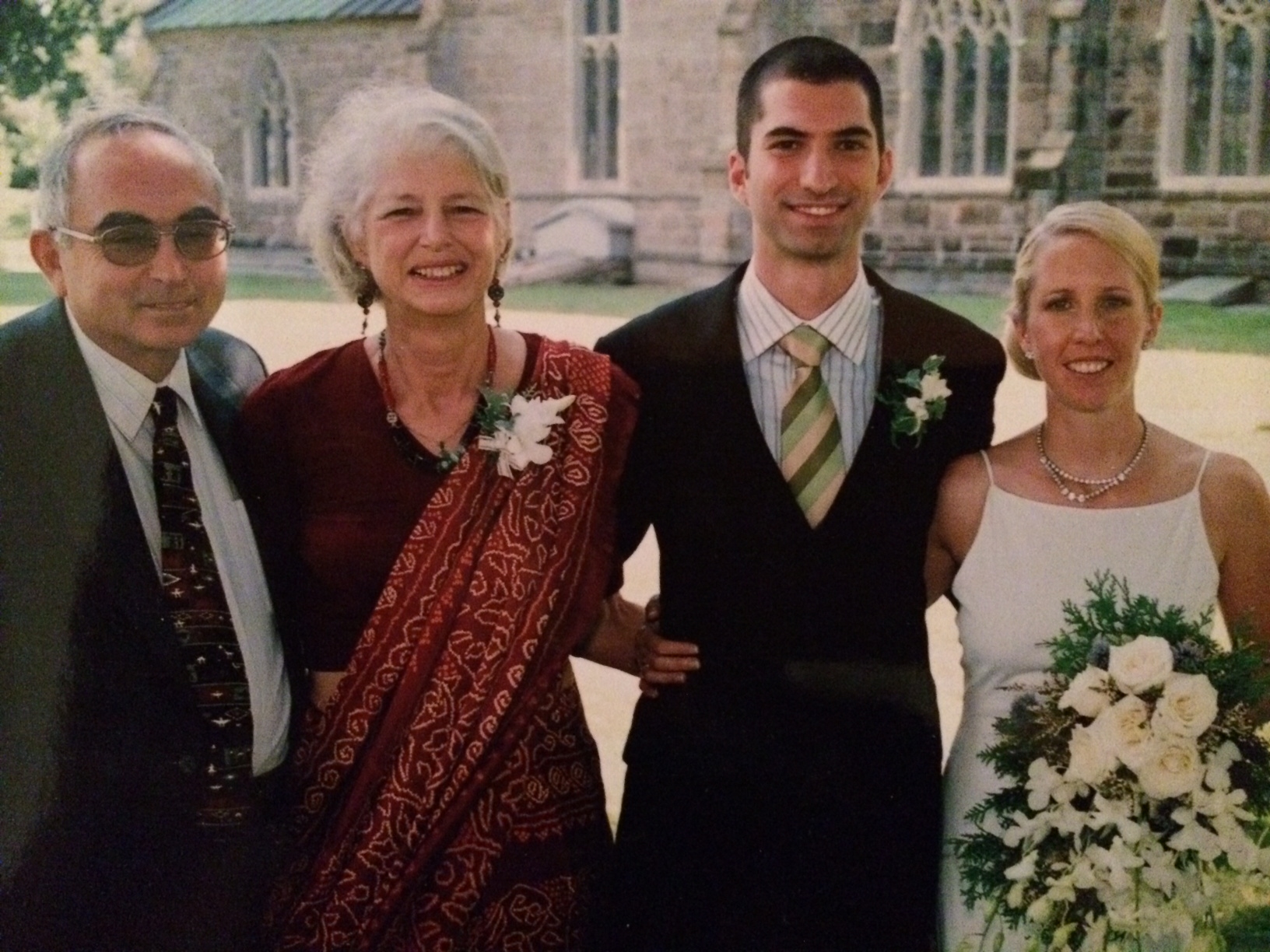

In April 2005 my boyfriend Jacques flew from Halifax to California to be with his mom Peg as she underwent surgery. She was convinced three months of stomach pain meant she contracted parasites on one of her trips overseas but her doctor insisted they open her up. Less than a year later, Peg was my mother-in-law and Jacques and I left our jobs in Canada to live with her in Napa. Peg had stage IV colon cancer. Here is what I learned as her caregiver…what every caregiver ought to know.

1. Your Opinions Don’t Matter

Peg refused surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and oncologists. Instead, she gave up wheat and meat, drinking her calories – about 400 a day – most of it kefir: a fermented milk drink made with a bacterial starter of kefir grains.

Three times a week, we drove an hour through wine country to a private clinic. No ordinary clinic: this one claimed to cure cancer and epilepsy using intravenous treatments of albumium: a protein produced by human livers and found in egg whites. Security was high. To enter the waiting room, the no-nonsense receptionist required official i.d. and disclosure of employment; officers of the law and government officials not permitted. Only once before leaving Peg for her 6 hour treatment, the receptionist allowed me to use the bathroom beyond the key-code door. The long hallway to the bathroom pulsated with a quiet anxiety and through an open door I glimpsed a young boy dressed in black lying in a tiny windowless room, an IV strapped to his arm.

Peg — the woman who fought traditional gender roles to achieve higher education and a lifetime of experience in foreign countries — didn’t matter to the clinic.

Peg — the dying woman with life-savings — interested the salesmen selling snake oil.

The injustice angered me.

She might as well ignite a bonfire of cash in the backyard three times a week for all the clinic did for her. But no matter: if these quacks were simply well-dressed pirates stealing the pennies off a dead man’s eyes, Peg’s family still insisted we support her journey.

Because it wasn’t about if the treatments worked; it was about allowing Peg a last experiment, a last surge of hope.

2. You work full-time hours

Tension in the house reached an all-time high by March 2006. Three months after our move to California, we were on a round-the-clock schedule.

While Peg was still able to walk and visit the clinic, we cleaned her childhood home. We started by clearing paths through generations of clutter: decades of bags filled with paperback books, craft supplies, dusty wine bottles, wooden trinkets, boxes – you name it we moved it – to reach the table of medications, vitamins, and ayurvedic concoctions. We pushed aside stacked jars and bottled fruit littering the kitchen floor to blend kefir shakes. We made sure Peg wouldn’t trip as she walked to the bathroom and the lazy boy in the living room. Jacques and I met in the kitchen to eat a late dinner surrounded by cookware, stacked chairs and tables, utensils hanging from the walls, fruit baskets and dying jade plants hanging from the ceilings, family life bringing us closer than we ever imagined.

We ran errands around northern California looking for Tachyon drops to charge Peg’s water with what the company claimed were ‘subtle organizing energy fields’ to bypass blockages and turn your body into a super conductor. We grocery shopped. We went on wild goose chases for tinctures. We fielded calls. We welcomed guests. We cleaned clothes and sheets. We bought and eventually administered medication.

The tumors spread, Peg’s liver began to shut down and we rented a hospital bed to help her mobility and reduce bed sores. That narrow bed squeezed between her queen size bed and antique bureau became Peg’s universe as she morphed from a strong, opinionated woman to a bony shadow unable to make sense of a morphine-muffled world. In the weeks before she died, a tumor grew in her cheek, pushing on her eyeball. Her eyes large blue marbles – drained of their past light – closed as she held my hand, her words slurring as she whispered “It’ll be a blessing when I go.”

Peg hated the dark confusion of the morphine, becoming afraid of the long nights. It was then we began to measure life in twenty-four hour shifts, someone always at Peg’s bedside. The hiss of the oxygen machine and the rainy winter nights closed in on us until the relief of dawn’s grey light outlined Peg’s sleeping body; the shape of pill bottles, Kleenex boxes, water bottles, dirty juice glasses appearing in the light and we’d shake off the night and busy ourselves with cleaning up before starting the next round of shakes, medication, sheet and clothing changes, phone calls, and visitors.

3. Death is Anti-Climatic

One day in late March just as the magnolias began to bloom and the smell of roses drifted inside from the garden, Peg slipped away in her sleep. We called hospice and a woman came to help me clean and dress Peg’s body for cremation. As we moved her, Peg groaned and my heart jumped into my throat. “She’s not dead. She’s ok.” But it was just a release of air from her windpipe.

The hospice worker and I changed Peg into a burgundy shirt and flower skirt and wrapped her in the Tibetan flag set aside a month beforehand. Two young men from the crematorium showed up an hour later. I remember them as Grim Reapers. Faceless. Quiet. Detached. Lifting her onto the stretcher, rolling her down the hallway through the door to what looked like a small moving truck, its doors slamming shut with finality. I drifted behind them, barefoot, wandering down the sidewalk until the driver jumped behind the wheel. I opened my mouth to yell for them to stop. But instead I just stood on the concrete watching the truck disappear around the corner, not wanting to go back inside the house ever again.

The next night we picked up pizza. Jacques drove over the speed limit, braking suddenly at red lights, neither of us speaking. The purple hills of Napa’s twilight reflected in the river like every other evening. At the pizza place, people waited for their orders; kids talked on their cell phones; arcade games repeated their jingles. A woman made a fuss, arguing the cashier shorted her fifty cents. And the world continued on just like nothing had happened.

4. Grief Wears Many Hats

There was no cremation viewing. There was no funeral.

I cried a little here and there but I wept the first time we visited Peg’s site at Arlington National Cemetery six year later.

My immediate grief showed in other ways. Translucent spots floated in front of me, the first sign of migraines. I woke in the middle of the night, jumping out of bed in the dark, gasping for air wondering where I was, who was snoring next to me. I’d panic, stumbling around until I grasped a curtain or a door handle to let in some light.

I felt relief it was all over. I experienced intense guilt over the relief. And I still have full-color heart-pounding nightmares where Peg visits me, angry at me for cleaning out her house after she died.

In his widely acclaimed book The Will of the Storyteller, Albert Frank writes about the period of adjustment after an illness, a period of loss:

To adjust too rapidly is to treat the loss as simply an incident from which one can bounce back. Only through the mourning can we find a life on the other side of loss. The losses you go through are real, and no one should take these away from you. They are a part of your experience, and you are entitled to them.

5. Lessons Become Clear Later On

When you turn the page on life-changing circumstances, it’s not an epilogue; it’s the next chapter. But turning that page takes a long time — much longer than I expected.

Mallory wrote a post entitled The Process of Surviving earlier this year. It places illness and survival as ongoing themes throughout life, not chapters we move on from after someone dies or after we receive a clean bill of health.

The lessons I learned as a caregiver changed me forever. I grieved for many years; in some ways I always will but now eight years after those months with Peg, I’m thankful I had the chance to hold her hand, to be the last person to help her after death, the last one to touch her before she left our lives forever. And the lessons I learned from her final months are with me for a lifetime.

—

Jenny is a Canadian living in Virginia with her husband, two kids, and two black cats. Her latest book Who I Am: American Scar Stories launches 2 June 2014.

To find out more information or to join the American Scar Stories community, check out www.jennycutlerlopez.com.

You can find quotes, portraits, and scar info at the book’s official Facebook page.

Semi-humorous and informative tweets for readers and writers @jcutlerlopez.